All of our recommendations, unless specified, relate to acute COVID-19 in adults.

Some of our recommendations vary according to the severity of COVID-19 illness. Definitions of the categories are based on World Health Organization (WHO) criteria and can be viewed by clicking the plus (+) signs below.

Recommendation:

We recommend inhaled budesonide in patients with non-severe (mild or moderate) COVID-19 without hypoxia who have been unwell for more than 3 days and are at risk of severe disease (for example, due to advancing age, co-morbidities and/or laboratory parameters). We do not have enough evidence to make a recommendation for patients with severe or critical COVID-19.

Date of recommendation: 21st June 2021

A conditional recommendation is one for which the panel is less confident about the balance between desirable and undesirable effects of the intervention, or other aspects, such as cost and feasibility.

Definition of non-severe:

NO features of severe or critical illness (see below). For some interventions this group may be divided into:

Mild illness

- Symptomatic (any acute COVID-19 related symptoms)

- AND respiratory rate <24/min

- WITHOUT pneumonia or hypoxia

Moderate illness

- Pneumonia (clinical or radiological) OR hypoxia (SpO2 <94% in adults with no underlying lung disease)

- AND respiratory rate ≤30/min

- AND SpO2 ≥90% on room air

The evidence from two randomized controlled trials suggests that inhaled budesonide may reduce time to recovery in patients with mild COVID-19. In one of the trials it probably reduced the risk of need for oxygen support in patients with mild COVID-19, though it probably had little to no effect on risk of progression to hypoxia in the other trial. It may result in a slight reduction in the risk of hospitalisation or death. While the evidence was very uncertain about adverse events in these trials, inhaled budesonide at this dose is a safe intervention when used for short courses (such as up to 14 days) in other conditions. The larger trial (PRINCIPLE [8]) of inhaled corticosteroids recruited participants at an average of six days from symptom onset and older participants (mean age 63 years), 81% of whom had comorbidity. Therefore, the group advise prioritisation of inhaled corticosteroids in patients later in the illness course.

The expert working group noted that systemic corticosteroids have been shown to reduce mortality in patients with severe and critical COVID-19. Hence in this group of patients, it would be appropriate to use systemic corticosteroids rather than inhaled corticosteroids, which have not been trialled in this group. The beneficial effect of systemic corticosteroids is absent in patients with non-severe COVID-19 and in those early in the illness (within seven days from onset) and there were concerns about harm.

Extrapolating these factors and the uncertainty of evidence into account, we recommend that inhaled budesonide should only be used in patients with non-severe disease without need for oxygen therapy, particularly people with risk factors for progression (such as advancing age or comorbidity), moderate disease, and ongoing acute respiratory COVID-19 symptoms at more than 3 days of symptom onset.

Date of latest search: 28th April 2021.

Date of completion of Summary of findings table and presentation to Expert Working Group: 12th May 2021.

Date of planned review: 28th January 2022

Evidence synthesis team: Avinash A Nair, Jefferson Daniel, Richard Kirubakaran, Priscilla Rupali and Bhagteshwar Singh.

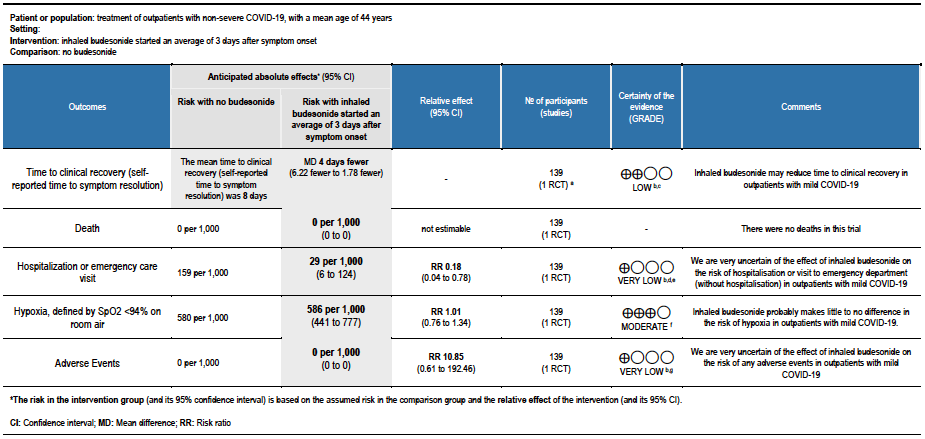

Summary of findings table 1: Inhaled budesonide started an average of 3 days after symptom onset compared to no budesonide for treatment of outpatients with non-severe COVID-19, with a mean age of 44 years

Explanations:

a. STOIC trial [7]

b. Downgraded by 1 level for serious risk of bias. The STOIC trial was assessed to be at high overall risk of bias (high risk of bias in measurement of outcome and selection of the reported result).

c. Downgraded by 1 level for serious imprecision. The lower boundary of the CI is 1.78, which may not be considered a clinically appreciable benefit.

d. Downgraded by 1 level for serious indirectness, as the study was conducted in one country and only recruited between surge situations. The pathway for referral for urgent care was very specific and might not be relevant to other countries

e. Downgraded by 1 level for serious imprecision. The optimal information size was not met for this outcome.

f. Downgraded by 1 level for serious imprecision, due to CI overlapping no effect and inability to exclude serious benefit or serious harm.

g. Downgraded by 2 levels for very serious imprecision, due to small absolute number of events, CI overlapping no effect and inability to exclude serious benefit or serious harm.

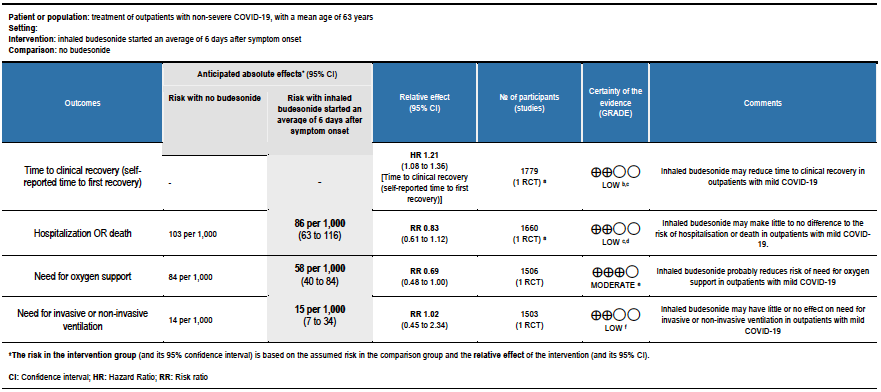

Summary of findings table 2: Inhaled budesonide started an average of 6 days after symptom onset compared to no budesonide for treatment of outpatients with non-severe COVID-19, with a mean age of 63 years

Explanations:

a. PRINCIPLE trial [8]

b. Downgraded by 1 level for serious risk of bias, due to early reporting of results for a time-to-event outcome without confirmation of meeting power calculation, and the effect of no placebo on an unblinded participant-reported outcome.

c. Downgraded due to reporting bias: the interim analysis was published using a subgroup of participants, and results were not published for all outcomes.

d. Downgraded by 1 level for serious imprecision, due to CI including no effect, and inability to exclude important benefit or serious harm with budesonide.

e. Downgraded by 1 level for serious imprecision, due to inability to exclude no benefit from budesonide.

f. Downgraded by 2 levels for very serious imprecision, due to few events, and CI including no effect, and inability to exclude important benefit and very serious harm with budesonide

Corticosteroids are potent anti-inflammatory agents [1], used widely in medicine. Inhaled corticosteroids have been the cornerstone of treatment in chronic respiratory diseases like asthma for decades [2], in whom they have been shown to reduce the number and severity of exacerbations [3].

In studies in the present COVID-19 pandemic, in-vitro studies have shown that inhaled corticosteroids reduce the replication of SARS-CoV-2 in airway epithelial cells, in addition to the downregulation of expression of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 genes, which are critical for viral cell entry [4].

Systemic corticosteroids have been reported to reduce mortality and need for invasive ventilation in patients hospitalised with COVID-19 as demonstrated by the RECOVERY trial and subsequent trials [5].

It is likely that the beneficial effect of corticosteroids in severe viral respiratory infections is dependent on the selection of the right dose and duration. High doses may be more harmful than beneficial, especially in earlier disease [5], though this may be due to systemic effects, which might be avoided using local delivery to the respiratory epithelium, using the inhaled route.

Based on this, and interesting observations from observational studies of under-representation of patients with chronic respiratory diseases among patients with severe COVID-19 [6], multiple trials of inhaled corticosteroids in non-severe COVID-19 have been started. Two of these have reported, with resulting use of this intervention around the world [7;8].

This review aims to provide a summary of the available evidence from randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of inhaled corticosteroids for treatment of COVID-19, so the Expert Working Group can provide a recommendation to guide clinicians and researchers regarding appropriate use of this intervention.

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE (Pubmed) and Epistemonikos for RCTs of any publication status and in any language. We performed all searches up to 12th May 2021. We contacted researchers to identify unpublished and ongoing studies.

We planned to extract data for the following pre-defined outcomes:

- Critical (primary for this review):

- Time to clinical recovery (including self-reported)

- Need for hospitalisation

- Need for oxygen support

- Important (secondary):

- Need for invasive or non-invasive ventilation

- All-cause mortality

- Adverse events:

- All

- Serious

- Oral candidiasis

- Secondary lung infection (clinician defined bacterial pneumonia)

Two reviewers independently assessed eligibility of search results using the online Rayyan tool. Data extraction was performed by one reviewer, and checked by another, using a piloted data extraction tool on Microsoft Word. Risk of bias (RoB) was assessed using the Cochrane RoB v2.0 tool, with review by a second reviewer and then discussion of each trial’s judgments with a third senior reviewer. We planned to use risk ratios (RR) for dichotomous outcomes and mean differences (MD) for continuous outcomes, with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We planned to meta-analyse if appropriate, i.e. if outcomes were measured and reported in a similar way for similar populations in each trial, using random-effects models with the assumption of substantial clinical heterogeneity (the appropriateness of which would be checked by the Methodology Committee), and the I2 test to calculate residual statistical heterogeneity, using Review Manager (RevMan) v5.4. We used GRADE methodology to make summary of findings tables on GradeProGDT.

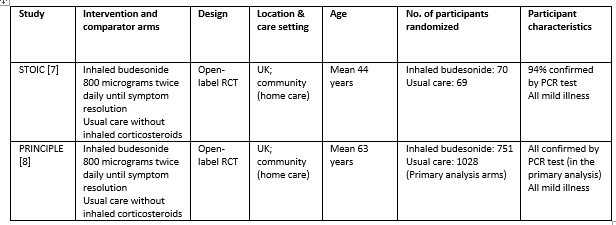

We found 1119 articles including 29 RCTs and 5 meta-analyses, of which only 2 RCTs matched the PICO question as pre-defined by the expert working group [7;8]. The trials included a total of 1799 symptomatic participants, all of whom were adult outpatients in the UK with illness satisfying the Guidelines Group’s criteria of mild COVID-19. However, as the trials did not report any outcomes in a way that allowed them to be pooled, meta-analysis was not performed. Additionally, as the trials recruited participants with substantially different characteristics, two separate summary of findings tables were made, one for each trial. Each trial and its results are described below; characteristics of the trials are summarised in the Summary of characteristics of included trials table.

STOIC trial

The STOIC trial [7] was a community-based, open-label randomized trial with two arms: one with inhaled budesonide 800 micrograms twice daily using a dry-powder Turbohaler inhaler device (until resolution of symptoms) and the other received usual care without inhaled corticosteroids. Initially, 73 participants were randomized to each arm; 70 and 69 completed the trial and were included in the primary analysis, respectively. All patients were aged 18 years or above, and had mild COVID-19 within 7 days of symptom onset. All the baseline characteristics were similar, including symptoms, age, comorbidities and positivity for PCR for SARS-CoV-2 (94% overall). The primary outcome of the study was COVID-19 related urgent care visit, which included emergency department visit and hospitalisation. This was a composite outcome and a breakdown was not available.

The secondary outcomes were clinical recovery (self-reported symptom resolution), intensity of viral symptoms (questionnaire based), oxygen saturations measured using a pulse oximeter and temperature (both self-monitored) and SARS-CoV-2 viral load.

The mean age of participants was 44 years, and they were enrolled at a median of 3 days since symptom onset. They had a median of 1 pre-existing comorbidity.

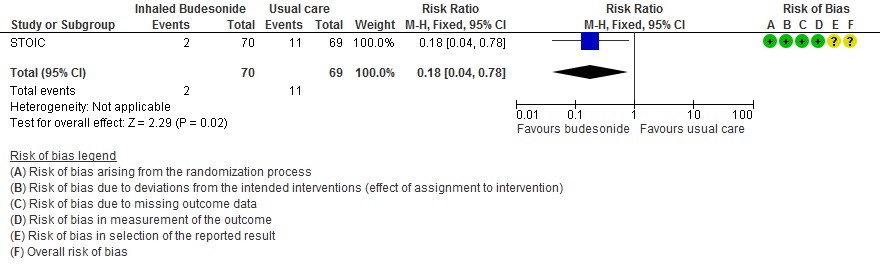

The intention to treat (ITT) analysis showed that urgent care visits occurred in 2 participants (3%) in the inhaled budesonide group versus 11 (15%) in the usual care group.

The self-reported time to clinical recovery was an average of 1 day shorter in the inhaled budesonide group: median 7 days (95% CI 6 to 9) versus 8 days (95% CI 7 to 11).

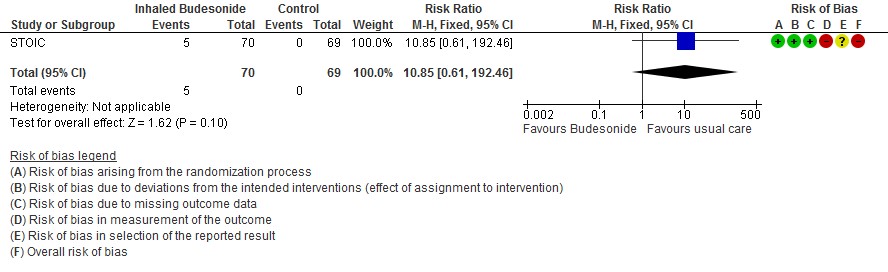

The other outcomes were similar in both the groups; there were 5 adverse events reported in the inhaled budesonide group which were mild (4 sore throat, 1 dizziness), thought the dizziness prompted discontinuation of the inhaled budesonide.

We found potential risks of bias across all domains except domain 2, which investigates deviations from the intended intervention. Risk of bias for each domain per trial and outcome is displayed alongside the Forest plots below.

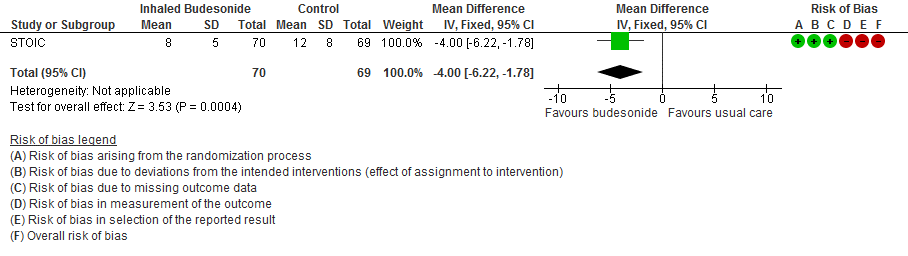

STOIC (mean age 44 years, median 3 days from symptom onset, mild COVID-19):

- Inhaled budesonide may reduce time to clinical recovery in outpatients with mild COVID-19, with a mean difference of 4 days fewer in the inhaled budesonide vs. the usual care group (95% CI 6.22 fewer to 1.78 fewer; low certainty in the evidence).

- There were no deaths in this trial.

- The effect of inhaled budesonide on the risk of hospitalisation or visit to emergency department (without hospitalisation) is very uncertain in outpatients with mild COVID-19 (RR 0.18; 95% CI 0.04 to 0.78; very low certainty in the evidence).

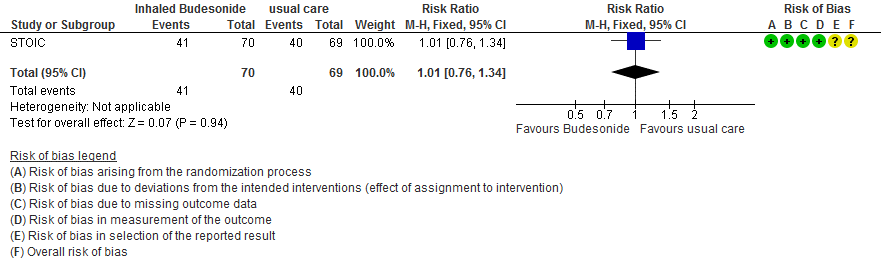

- Inhaled budesonide probably has little to no effect on risk of progression to hypoxia (<94% oxygen saturation breathing room air) in outpatients with mild COVID-19 (RR 1.01; 95% CI 0.76 to 1.34; moderate certainty in the evidence).

- We are very uncertain of the effect of inhaled budesonide on the risk of adverse events in outpatients with mild COVID-19 (RR 10.85; 95% CI 0.61 to 192.46; very low certainty in the evidence).

PRINCIPLE Trial

The PRINCIPLE trial [8] was available in a pre-print, non-peer reviewed document reporting results from an interim analysis. While also an open-label randomised trial comparing inhaled budesonide with usual care in people with mild COVID-19, in comparison to the STOIC trial, this trial enrolled older people (>65 years age, or >50 years with comorbidities), who could have had symptom onset up to 14 days before enrolment. The dose and administration method was the same as the STOIC trial (800 micrograms twice daily via a dry-powder Turbohaler), but 14 days of use was planned.

The trial recruited 751 participants in the inhaled budesonide arm versus 1028 in the usual care arm, who had a positive RT-PCR test for SARS-CoV-2. The inhaled budesonide arm included 65.6% participants with an age above 65 years, compared to 58.5% in the usual care arm. Overall average age was 63 years. Of the usual care arm, 15% had chronic respiratory diseases, compared to 8.4% in the inhaled budesonide arm. All the other baseline characteristics were similar. The median time from symptom onset to enrolment was 6 days. Around 80% of participants had comorbidity.

The co-primary outcomes were time to self-reported recovery and a composite outcome of hospitalisation or death due to COVID-19.

The secondary outcomes were how well the participants felt (self-reported ratings on a 10-point scale), incidence of contact with health services, oxygen administration, intensive care unit admission and mechanical ventilation.

The median time to self-reported recovery was 11 days in the inhaled budesonide arm versus 14 days in the usual care arm. The incidence of hospitalisation or death was 59/692 (8.5%) in the budesonide arm versus 100/968 (10.3%) in the usual care arm.

PRINCIPLE (mean age 63 years, median 6 days from symptom onset, mild COVID-19):

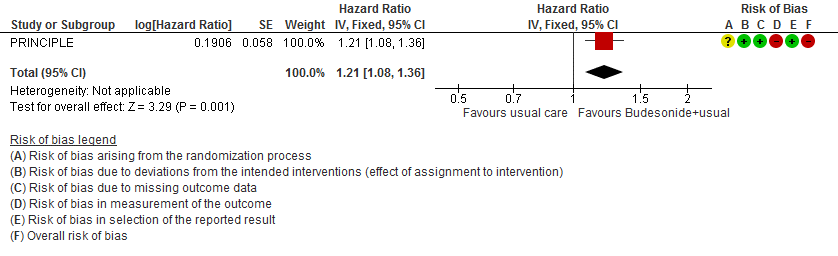

- Inhaled budesonide may reduce time to self-reported clinical recovery in outpatients with mild COVID-19 (hazard ratio (HR) 1.21; 95% CI 1.08 to 1.36; low certainty in the evidence).

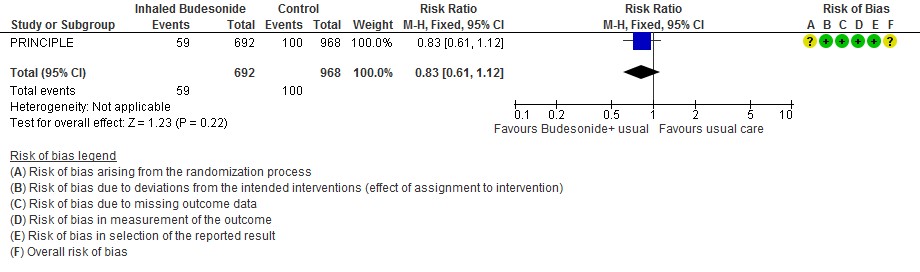

- Inhaled budesonide may result in little to no difference in the risk of hospitalisation or death in outpatients with mild COVID-19 (RR 0.83; 95% CI 0.61 to 1.12; low certainty in the evidence).

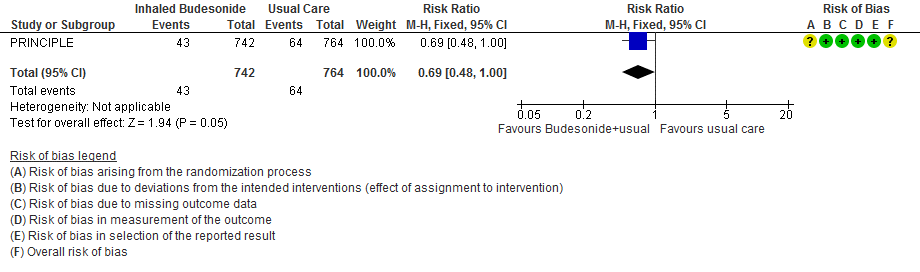

- Inhaled budesonide probably reduces risk of need for oxygen support in outpatients with mild COVID-19 (RR 0.69; 95% CI 0.48 to 1.00; moderate certainty in the evidence).

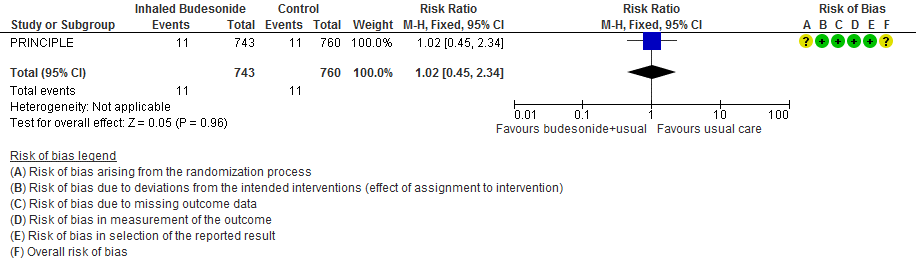

- Inhaled budesonide may have little or no effect on need for invasive or non-invasive ventilation in outpatients with mild COVID-19 (RR 1.02; 95% CI 45 to 2.34; low certainty in the evidence).

- RR of intensive care unit admission was 0.54 (95% CI 0.24 to 1.21).

Forest plots

STOIC trial

Time to clinical recovery

Hospitalization and ED visits

Progression to hypoxia (SpO2 ≤94% in 14 days)

Adverse events

PRINCIPLE

Time to clinical recovery

Hospitalization or death

Need for oxygen support

Need for invasive mechanical ventilation

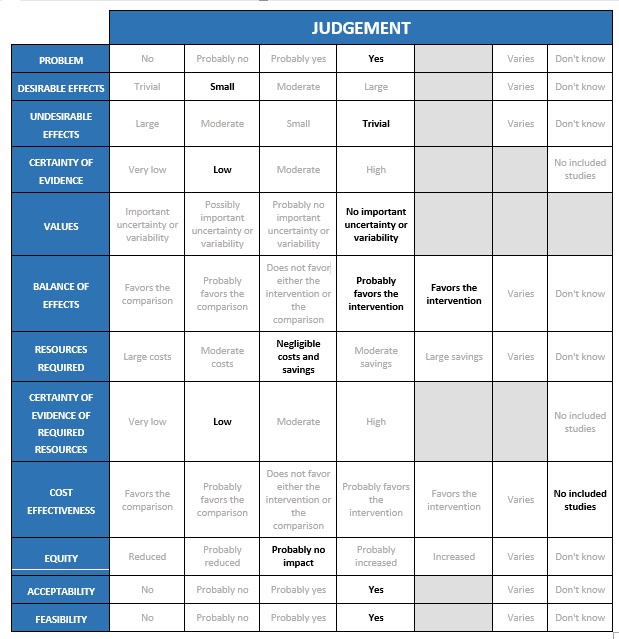

The Antiviral Expert Working Group met on 12th May 2021 to consider inhaled corticosteroids as a treatment for COVID-19. A summary and then more detailed explanations of their judgements follow.

Summary of judgements

Problem

As established through the intervention question prioritisation process, inhaled corticosteroids are being used very widely in India currently, as one of few candidate interventions for outpatients with non-severe COVID-19, and due to promising results of the two trials being considered in this review.

Desirable effects

The group considered the following results from the two trials to reflect trivial or small desirable effects, settling on small.

From the STOIC trial (mean age 45 years, median 3 days from symptom onset, mild COVID-19, median 1 comorbidity):

- Time to clinical recovery: mean difference 4 days lower with budesonide (95% CI 6.22 lower to 1.78 lower)

- No deaths

- Hospitalisation or visit to emergency department (without hospitalisation) RR 0.18 (0.04-0.78)

- Lower oxygen saturations ≤94% RR 1.01 (0.76-1.34)

From the PRINCIPLE (mean age 63 years, median 6 days from symptom onset, mild COVID-19, 80% with comorbidity):

- Time to clinical recovery HR 1.21 (1.08-1.36)

- Hospitalisation or death RR 0.83 (0.61-1.12)

- Oxygen support RR 0.69 (0.48-1.00)

- Invasive or non-invasive ventilation RR 1.02 (0.45-2.34)

- ICU admission RR 0.54 (0.24-1.21)

Undesirable effects

The group considered that in the STOIC trial, the risk of any adverse events was reported as a risk ratio (RR) of 10.85 (95% CI 0.61-192.46), but these events were all mild, so this reflected trivial or small undesirable effects, with consensus on trivial being agreed finally. Comparative results on adverse events or effects were not reported in the PRINCIPLE trial.

Certainty of evidence

Using GRADE methods, the evidence synthesis team rated the certainty in the evidence as low overall; the expert working group agreed. However, this might be very low for some subgroups of patients, such as younger adults with no comorbidity. The group also discussed that the participants in the two trials were very different, so the biological plausibility of benefit would vary in each group (in terms of stage of illness and risk of progression to severe illness). It was also acknowledged that the lack of placebo inhaler could have influenced a subjective outcome like time to clinical recovery as reported by participants, which might not be captured fully in the GRADE assessment. Though the GRADE assessment concluded moderate certainty for the secondary outcomes relating to oxygenation/oxygen need, the STOIC trial was not powered for this outcome, and this was clearly labelled as an interim analysis in PRINCIPLE. Finally, the group discussed that evidence was very uncertain about adverse events in this context, though this intervention has a well-established safety profile for other conditions.

Using GRADE methods, the evidence synthesis team rated the certainty in the evidence as low overall; the expert working group agreed. However, this might be very low for some subgroups of patients, such as younger adults with no comorbidity. The group also discussed that the participants in the two trials were very different, so the biological plausibility of benefit would vary in each group (in terms of stage of illness and risk of progression to severe illness). It was also acknowledged that the lack of placebo inhaler could have influenced a subjective outcome like time to clinical recovery as reported by participants, which might not be captured fully in the GRADE assessment. Though the GRADE assessment concluded moderate certainty for the secondary outcomes relating to oxygenation/oxygen need, the STOIC trial was not powered for this outcome, and this was clearly labelled as an interim analysis in PRINCIPLE. Finally, the group discussed that evidence was very uncertain about adverse events in this context, though this intervention has a well-established safety profile for other conditions.

Values

The group felt it likely that patients, clinicians and policymakers would see these outcomes as important.

Balance of effects

The evidence is very uncertain about undesirable effects. While there is low certainty in a small desirable effect overall, the balance might vary between groups. The group settled on ‘favours the intervention’ for older age groups, and those with other risk factors for progression, but ‘probably favours the intervention’ for younger patients without risk factors for severe COVID-19.

Resources required

The trials used a Turbohaler dry-powder inhaler which is not available in India. The cost of a metered-dose inhaler (MDI) that delivers an aerosol from a high-pressured chamber plus a spacer device is usually 600-800 rupees. Rotacap and Rotahaler dry-powder inhalers are around 150-200 rupees for a 14-day course. Use of a nebuliser plus nebules is a more expensive option. The group discussed whether the cost may be moderate or negligible, but acknowledged that this would depend on the delivery device and the care setting or socioeconomic group.

Certainty of evidence of required resources

While no studies reported cost of the intervention, there is knowledge within the group regarding costs of the intervention, and how this will vary by device and stakeholder perspective.

Cost effectiveness

No studies examined cost-effectiveness. Evidence of the effectiveness of the intervention for this indication is of low certainty overall, which might make confident calculation of cost-effectiveness difficult.

Equity

The intervention would be accessible to most people as there are a few options for its delivery. Some people may be unable to use the intervention, but this could be overcome by training in its use. Therefore, this is likely to have no impact on health equity.

Acceptability

The intervention was felt to be acceptable to patients, clinicians and policymakers.

Feasibility

Ability to use an inhaler might be a barrier but this could be overcome. Cost is not prohibitive if specific devices are used.

The Group recommends the dose used in the trials: 800 micrograms of budesonide twice daily (total daily dose 1600 micrograms). The recommended duration is until symptom resolution or a maximum of two weeks.

This is an easily implementable intervention for all age groups that have no contraindications for the use of inhaled corticosteroids. Cost and ability to achieve effective delivery of the drug can be optimised through use of a metered dose inhaler device with a spacer, or using one of the dry-powder inhaler devices available in India. Training of the patient is essential, but quite simple, and should include use of these devices in a way to achieve maximal delivery of the drug to smaller airways, but also to reduce deposition in the throat which can lead to hoarseness and infections such as candidiasis.

As systemic corticosteroids are recommended for patients who need oxygen supplementation, we recommend strongly against use of inhaled corticosteroids for patients with severe or critical COVID-19. Among patients with non-severe illness, the two trials considered only included patients with mild COVID-19, though in the STOIC trial [7] around half did progress to having oxygen saturations below 94%.

As inhaled corticosteroids are used for COVID-19, real-world evidence from registries and studies should inform our knowledge, particularly of potential adverse events.

The benefit of corticosteroids in early disease demonstrated in the smaller STOIC trial [7] is somewhat surprising biologically (early in the disease there is usually less inflammation), and the larger PRINCIPLE trial [8] recruited patients who were on average later since onset of symptoms. Accordingly, the expert working group has advised that patients with non-severe disease who are later in the illness course should be the focus of this intervention. However, the relative effect of inhaled corticosteroids at different time since onset of symptoms is an area that should be focused on in further research. Further exploration of potential differential benefit in patients with vs. without risk factors for progression to severe COVID-19, and those with vs. without elevated markers of inflammation such as C-reactive protein, is also warranted. Additionally, the evidence was very uncertain for adverse events, so future research must address this gap.

- Coutinho AE, Chapman KE. The anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive effects of glucocorticoids, recent developments and mechanistic insights. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2011 Mar;335(1):2–13.

- Barnes PJ. Inhaled Corticosteroids. Pharmaceuticals. 2010 Mar 8;3(3):514–40.

- O’Byrne P, Fabbri LM, Pavord ID, Papi A, Petruzzelli S, Lange P. Asthma progression and mortality: the role of inhaled corticosteroids. Eur Respir J. 2019 Jul;54(1):1900491.

- Halpin DMG, Singh D, Hadfield RM. Inhaled corticosteroids and COVID-19: a systematic review and clinical perspective. Eur Respir J. 2020 May;55(5):2001009.

- The RECOVERY Collaborative Group. Dexamethasone in Hospitalized Patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021 Feb 25;384(8):693–704.

- Lipworth B, Kuo CR, Lipworth S, Chan R. Inhaled Corticosteroids and COVID-19. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020 Sep 15;202(6):899–900.

- Ramakrishnan S, Nicolau DV Jr, Langford B, et al. Inhaled budesonide in the treatment of early COVID-19 (STOIC): a phase 2, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2021 Apr 9:S2213-2600(21)00160-0. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00160-0.

- PRINCIPLE Collaborative Group, Yu L, Bafadhel M, et al. Inhaled budesonide for COVID-19 in people at higher risk of adverse outcomes in the community: interim analyses from the PRINCIPLE trial. medRxiv; 2021. DOI: 10.1101/2021.04.10.21254672.

Covid Management Guidelines India Group - Anti-inflammatory Working Group. Inhaled Corticosteroids. Covid Guidelines India; Published online on June 21, 2021; URL: https://indiacovidguidelines.org/inhaled-corticosteroids/ (accessed ).